Pain education as it is taught in the CRAFTA® curriculum

What is PNE?

Pain education, “pain neuroscience education (PNE)” or “Explain Pain” is a therapeutic tool highly recommended by several institutions especially by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). In its revised curriculum for pain management it is described as a major competence for physiotherapists to work with patients in chronic as well in acute pain states (IASP, 2018).

The authors of this curriculum are now going to shift the content from a knowledge based into a more competence-based structure. That means the therapist is not just taught in the mechanisms of nociception and pain but also in the way how to teach this knowledge. To fulfill this task, the therapist needs an empathic way and certain communication skills to guide the patient through this very complex field (O´Sullivan, 2012).

The evidence and clinical reasoning.

Several studies show positive effects for students and therapists that get to know this knowledge and work on that competences of pain education leading to a more biopsychosocial view and acting in the management of patients in pain (Colleraya et al, 2017; Louw et al, 2017). But the evidence is also quite remarkable regarding its effects on affected persons. The data show less use of medication, quicker recovery after operations and positive rehabilitation outcomes in chronic pain states (Louw et al, 2011; Meeus et al, 2010; Moseley, 2004).

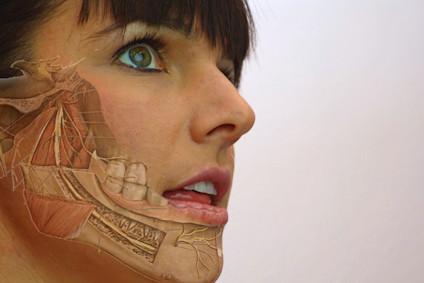

The CRAFTA® education program, with its biopsychosocial approach in the assessment and treatment of craniofacial, craniomandibular and neuropathic disorders, fulfills the ideas of the described IASP-curriculum already in the foundation courses. Besides the specific development of treatment skills and techniques, it is a major target to assess and understand the patient in a holistic point of view. Via the clinical reasoning process, the therapist should be able to have a functional, structural, activity- and participation-oriented comprehension of the patients’ issues.

Evidence based knowledge from the neuroscientific field and psychosocial oriented declaring models are used to explain the several pain mechanisms. Hereby the mature organism model, described and developed by Louis Gifford (1998) is a main model to first teach the therapist so that he or she then can teach the patient. Teaching patients in the neurobiology of pain according to clinical behavior and the presentation of pain does decrease the threatening values of pain and pain-sensation. It also has an influence on the emotional and cognitive aspects of pain (Melzack, 2005).

A foundation is made through understanding in making choices in relation to accompany the pain experience. This leads to an adequate way in cooperation with pain and should avoid deconditioning processes, hence lead to a normalization in participation and an increase in the level of activities. This is mainly possible if the skilled therapist offers the patient in a shared decision-making process to learn about the physiology of pain and its effects on the human organism (Moseley & Butler, 2017).

CRAFTA® contents.

The Key points in the CRAFTA® concept regarding to the clinical reasoning process and pain are (excerpt):

- Detect tissue-oriented sources (structures)

- Differentiate nociceptive, neuropathic and central-maladaptive processing (nociplastic) mechanisms

- Recognize psychosocial components – yellow flags:

- Duration of complains – do they get along with wound-healing-mechanism?

- Maladaptive parafunctions: bruxism, chewing fingernails, bracing in certain situations, etc.

- Lack in nonverbal communication due loss of facial expression capability as result of ongoing facial pain and/or headache

- Stress and behavior

- Affective/emotional relationships

- Influence of family work conditions and co-workers

- Capture output mechanisms:

- Neuro-vegetative reactions

- Neuro-endocrine dysfunctions

- Neuro-immunological conspicuities

- Motor output (coordination deficits, loss of strength, raised muscle tension)

The understanding of pain, but also a structure-oriented knowledge, will help the patient to avoid the development of catastrophizing and resulting fear avoidance behavior (Main & Spanswick, 2000; Vlaeyen et al, 2004). Regarding the pain in acute and/or threatened tissue damage the patient is enabled to develop adequate coping skills to restore function and requested participation levels.

Understanding the biology of pain reduces the threatening values of pain and improves the management. There is strong clinical evidence that it is possible for each individual patient to learn and understand the neurobiology of pain (Moseley, 2003).

Management strategies to consider:

- General:

- Hands on vs. hands off

- Time quota with short term and long term aims

- Physical and psychological desensitization

- Concepts with evidence based medicine background:

- Exercise to improve function (Bennell et al, 2016)

- Active contribution patient (Harding et al, 2005)

- Feedback and commitment therapy plan (Vlayen et al, 1995)

- Pacing (McCracken & Samuel, 2007)

- Graded exposure (Wicksell et al, 2008)

- Lower cognitive behaviour to fear of movement (Crombez et al, 1999)

- Graded Motor Imagery and Facial Emotion Recognition (von Piekartz & Mohr, 2014)

The clinical implication.

Most of the described tools, skills, techniques or approaches are part of the CRAFTA® curriculum that has the ambition to be state of the art concerning evidence-based practice and medicine. One of the main messages in pain education is that pain nowadays has to be understood as an output of the brain influenced by various biological and psychosocial factors (Puentedura & Louw, 2012). Those factors are thought to be certain threads to the organism, and pain is the protective answer as long it makes sense and works in an adaptive form. As soon those threads have an overwhelming impact it might lead to maladaptive mechanisms of the central nervous system including peripheral and central sensitization or so called positive symptoms like hypersensitivity and allodynia (Flor, 2000).

Though there are good results in the therapeutically use of pain education, it seems like there are even better effects if it is included as an additional tool in the therapeutic process (Louw et al, 2016). Combined with the already described management strategies it might lead to far more effectiveness and efficacy. In the advanced courses of CRAFTA®, and especially in the facial expression course, the elements of graded exposure and graded motor imagery can be developed under supervision in theory and practice (physioedu.com), especially for orofacial pain and dysfunction. Those courses as well are based on current scientific knowledge to pain education and therapeutic tools for chronic facial pain and headache sufferers (von Piekartz, Puenteduran & Louw, 2018)

What´s in it for the patients?

In commitment with the patient, CRAFTA®-therapists can play an important part to facilitate desensitization of physiological and psychological issues regarding to unpleasant sensory and emotional experiences. Clinical reasoning determines adequate assessments and treatment-strategies. During the therapy process learning moments are included to pain beliefs, pain behavior, cognitive values and coping styles.

Multi-Professionalism in CRAFTA®.

The craniofacial region is the main focus of CRAFTA®. It is a remarkable region with many sensory functions cooperating and depending on each other. Though it is a complex area with possible dysfunction patterns, pain and disabilities it can be managed. One main characteristic in the CRAFTA® courses is the multimodal approach due to these several disorders. Cognitive-functional/behavioral techniques and education are one part of the curriculum, especially to de-catastrophize a certain situation. However, it is very clear for CRAFTA®-therapists, in case of multi-causality or severe psychological dysfunctions, to get in contact or collaboration to other professions like medical doctors, dentists, speech therapists and of course psychologists.

References:

- Bennell KL, Ahamed Y, Jull G, Bryant C, Hunt MA, Forbes AB, Kasza J, Akram M, Metcalf B, Harris A, Egerton T, Kenardy JA, Nicholas MK, Keefe FJ. (2016) Physical Therapist-Delivered Pain Coping Skills Training and Exercise for Knee Osteoarthritis: Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). May;68(5):590-602. doi: 10.1002/acr.22744.

- Collearya G, O’Sullivan K, Griffin D, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. (2017) Effect of pain neurophysiology education on physiotherapy students’ understanding of chronic pain, clinical recommendations and attitudes towards people with chronic pain: a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2017.01.006

- Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW, Heuts PH, Lysens R. (1999) Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain, March, Issue 80, pp. 329-39.

- Flor H. (2000) The functional organization of the brain in chronic pain. Progress Brain Res; 129: 313–322.

- Gifford L. (1998) Pain, the Tissues and the Nervous System: A conceptual model. Journal of Physiotherapy. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)65900-7

- Harding G, Parsons S, Rahman A, Underwood M. (2005) “It struck me that they didn’t understand pain”: the specialist pain clinic experience of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arthritis Rheum; 53 (5): 691-6. doi: 10.1002/art.21451

- International Association for the Study of Pain. (2018) IASP Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy. https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Curriculum

- Louw A, Puentedura EJ, Zimney K, Cox T, Rico D. (2017) The clinical implementation of pain neuroscience education: A survey study. Physiother Theory Pract. Nov;33(11):869-879. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2017.1359870. Epub 2017 Aug 18.

- Louw A, Zimney K, Puentedura E, Diener I. (2016) The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract 32(5):332–355

- Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. (2011) The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Dec;92(12):2041-56. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.07.198.

- Main CJ & Spanswick CC. (2000) Pain Management: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Churchill Livingstone. ISBN: 9780443056833

- McCracken LM & Samuel VM. (2007) The role of avoidance, pacing and other activity patterns in chronic pain. Pain, Band 130, pp. 119-125.

- Meeus M, Nijs J, Van Oosterwijck J, Van Alsenoy V, Truijen S. (2010) Pain physiology education improves pain beliefs in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared with pacing and self-management education: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Aug;91(8):1153-9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.04.020.

- Melzack R. (2005) Evolution of the neuromatrix theory of pain. Pain Practice, 5. 85-94.

- Moseley GL. (2004) Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. European J. of Pain, 8. 39-45

- Moseley GL. (2003) Unraveling the barriers to conceptualization of the problem in chronic pain. The actual and perceived ability of patients and health professionals to understand the neurophysiology. The J of Pain 4, 184-189.

- Moseley GL & Butler DS. (2017) Explain Pain Supercharged – The clinicians’ handbook. Noigroup publications. Neuro Orthopaedic Institute. Adelaide. AUS ISBN:978-0-6480227-0-1

- O`Sullivan P. (2012) It's time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain. Br J Sports Med March Vol 46 No 4. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.081638

- Puentedura EJ, Louw AA. (2012) Neuroscience approach to managing athletes with low back pain. Phys Ther Sport. 13: 123-133

- Vlaeyen J, De Jong J, Leeuw M, Crombez G. (2004) Fear reduction in chronic pain: Graded exposure in vivo with behavioral experiments. Ch 14 In Asmundson et al (Eds) Understanding and treating fear of pain. Oxford University Press: 313-343

- Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Rotteveel AM, Ruesink R, Heuts PH. (1995) The role of fear of movement/(re)injury in pain disability. J Occup Rehabil. Dec;5(4):235-52. doi: 10.1007/BF02109988.

- Von Piekartz H & Mohr G. (2014) Reduction of head and face pain by challenging lateralization and basic emotions: a proposal for future assessements and rehabilitation strategies. J Manual Manipulative Ther; 22: 24-35

- Von Piekartz H, Puentedura E, Louw A. (2018) Treating the brain in temporomandibular disorders In: Fernandez-de-las-Penas C & Mesa-Jimenez J. (editors) Temporomandibular disorders – Manual therapy, exercise and needling. Handspring Publishing. ISBN: 978-1-909141-80-3

- Wicksell RK, Ahlqvist J, Bring A, Melin L, Olsson GL. (2008) Can exposure and acceptance strategies improve functioning and life satisfaction in people with chronic pain and whiplash-associated disorders (WAD)? A randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Issue 37, pp. 169-18

Manual Cranial Therapy

Cranial manual therapy means: assessment and treatment of the cranium..

Read more..

Pain Education

“pain neuroscience education (PNE)” or “Explain Pain” is a therapeutic tool...

Read more..

Headache (HA) in children

What can the (specialized) physical therapist mean for this pain suffering group..

Read more..

Assessment Bruxism

Assessment and Management of Bruxism by certificated CRAFTA® Physical Therapists

Read more..

Clinical classification of cranial neuropathies

Assessment and Treatment of cranial neuropathies driven by clinical classification..

Read more..

Functional Dysphonia

Functional Dysphonia (FD) is a condition characterized by voice problems in the absence of a physical laryngeal pathology.

Read more..

Body Image and Distorted Perception

Body Image and Distorted Perception of One's Own Body – What Does This Mean?

Read more..

TMD in Children

TMD affects not only adults, but it also occurs frequently in children and adolescents..

Read more..