Assessment and Treatment of cranial neuropathies driven by clinical classification

History

During the CRAFTA® education the course members will be informed about the Taxonomy of DC/TMD, International Headache Association (IHS) and the International Association of Pain (IASP). These guidelines are very helpful to understand the diagnose process and the medical treatment on the background of external evidence. It is experienced by specialized craniofacial neuromusculoskeletal therapist that a large group of patients has multiple diagnosis and or the diagnosis still is not clear. In several cases specialized radiological measures like CT-scan, MRI ‘s are not sufficient supporting or clarify the mechanisms behind the patients ongoing craniofacial pain. From clinical evidence proposed neuromusculoskeletal assessment and treatment as during the CRAFTA® education is promoted, patients with long term cranio- facial dysfunctions and pain with multiple diagnosis may react rapidly positive.

During the CRAFTA® education the course members will be informed about the Taxonomy of DC/TMD, International Headache Association (IHS) and the International Association of Pain (IASP). These guidelines are very helpful to understand the diagnose process and the medical treatment on the background of external evidence. It is experienced by specialized craniofacial neuromusculoskeletal therapist that a large group of patients has multiple diagnosis and or the diagnosis still is not clear. In several cases specialized radiological measures like CT-scan, MRI ‘s are not sufficient supporting or clarify the mechanisms behind the patients ongoing craniofacial pain. From clinical evidence proposed neuromusculoskeletal assessment and treatment as during the CRAFTA® education is promoted, patients with long term cranio- facial dysfunctions and pain with multiple diagnosis may react rapidly positive.

Because of this experiences from different clinicians, CRAFTA® therapist try to classify head-face and neck pain according to the standard guidelines and taxonomies as decried above but parallel they try to manage a proposed clinical classification of cranio-neuropathic pain described by von Piekartz and Hall (2018).

Clinical classification of neuropathic pain by physical therapists is not new. Similar classifications are done in the upper and lower extremity with success and are proven as a fundamental basic for assessment and treatment of complicated, unclear diagnosed dysfunctions and pain (Schäfer et al 2014). In this statement we shortly will describe the clinical classification.

Clinical Sub- classification

Essentially, neural pain disorders can be broadly classified into 3 subgroups based on treatment likely to be effective (Schäfer et al 2009). Each can be identified with careful clinical examination and requires a different management approach.

These categories are:

- Neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity (NPSH)

- Compressive neuropathy (CN)

- Peripheral nerve sensitization (PNS)

1. Cranial neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity (NPSH)

These widespread and profound changes to the central and peripheral nervous system lies towards the extreme end of the chronic neuropathic pain continuum, and for the purposes of classification are defined as NPSH.

Recognition of the presence of NPSH can also be achieved through the use of screening tools such as the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) Questionnaire (Bennett 2001) shown in table 1.

Leeds assessment for neuropathic pain questionnaire (item score). A score greater than 12 indicates the presence of neuropathic pain.

| Item | |

| 1 | Does the pain have qualities like pricking, tingling, pins & needles? (yes = 5) |

| 2 | Does the skin in the painful area look different, mottled, red/pink? (yes = 5) |

| 3 | Does the pain cause the affected area to be abnormally sensitive to touch? (yes = 3) |

| 4 | Does your pain come in bursts - electric shocks, shooting or bursting (yes = 2) |

| 5 | Does the painful area feel like the skin temperature has changed – eg. hot or burning (yes = 1) |

| 6 | Is there evidence of mechanical allodynia? (yes = 5) |

| 7 | Is there evidence of pin prick hyperalgesia or hypoalgesia? (yes = 3) |

The Pain Detect Questionnaire(PDQ) may be an alternative.

NPSH has in most times the presence of 4 criteria increases the confidence in diagnosis (Treede, Jensen et al 2008). These criteria include

- pain within a distinct neuro-anatomically plausible distribution; Eg. facial dysesthesia during shaving or a shooting line of pain from proximal to distal in the mandible, consistent with the mandibular nerve;

- a history consistent with a lesion or a disease affecting the somatosensory system eg. after tooth extraction on the background of a whiplash associated disorder several years ago ;

- demonstration of altered bedside neurological function; For example facial skin conduction changes with unilateral anesthesia, lack of endurance or strength of the mandibular muscles or a “dry mouth”;

- abnormalities in the relevant confirmatory tests for the lesion or disease (Treede, Jensen et al 2008). Eg. reduced nerve conduction of the mandibular nerve or confirmation by MRI.

1.1.Appropriate Clinical Test

- Sensibility (light touch) - dysesthesia, allodynia or hyperalgesia

- Motor control: endurance, coordination, strength

- Reflexes (mostly multi-segmental)

- Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST)

Less appropriate are

- Palpation and neurodynamic testing

2. Compressive neuropathy (CN)

Compression inducing damage of the peripheral nervous system does not necessarily cause symptoms, as previously mentioned.

Even in the head- face region there may be evidence of neural conduction loss with minimal or no pain such as in dysarthria, hemifacial spasm, facial paralysis and diplopia (Haller, Etienne et al. 2016). The prevalence of asymptomatic nerve compression in the craniofacial region has been investigated in the CPA. For example there is evidence of microvascular compression of the trigeminal nerve in the CPA in healthy people, to a rate that was almost the same incidence as reported in symptomatic people with trigeminal neuralgia (Peker et al 2009). Another example is compression of the mental or inferior alveolar nerves, which causes a ‘numb chin syndrome’ (NCS) in some people without pain in the lower face (Smith et al 2015).

Clinically however, we find some patients have significant imaging and clinical signs of compression neuropathy (CN), correlated with significant pain but with an absence of positive features.

Such patients test negative on neuropathic screening tools such as the LANSS scale (Moloney, Hall et al 2013).These patients fit the IASP criteria for neuropathic pain and fall under the category of ‘definite neuropathic pain’ according to other published guidelines (Treede et al 2008). However, patients with CN appear to respond differently to physical intervention such as manual therapy when compared with individuals with NPSH, presumably because of a difference in underlying pain mechanisms.

2.1. Clinical Tests CN

- Not always painful;

- Associated with activity or postures that increase compression of the involved neural structures;

- Signs of a loss of neurological conduction (deep tendon reflexes, muscle power, skin sensation tests and vibration perception);

- Changed adjacent tissue of the nerve which may be influence movement behavior of the nerve;

- Recording of trigeminal somatosensory-evoked potentials and sensory neurography for damage of myelinated sensory fibers like thermal quantitative sensory testing (detection of trigeminal small-fiber dysfunction);

- Radiologic and electrodiagnostic evidence may support.

As imaging by itself is not that useful in diagnosis, a combination of all these factors is likely to improve diagnostic accuracy; - Neurodynamic test and palpation may be minimal or moderate positive.

2.2. Grading System for CN

Outlines a grading system for the identification of neuropathic pain with features of CN based on an evidence-based guideline. If all 4 criteria are met, a definitive diagnosis of neuropathic pain can be made, and the source of nerve compression of musculoskeletal origin identified to rule out other forms of nerve damage such as diabetic neuropathy (Treede, Jensen et al. 2008).

3. Peripheral nerve sensitization (PNS)

In this situation, nerve trunk connective tissue becomes sensitized, which might explain pain arising from minor nerve damage (Zusman 2008). Although the disorder involves the nerve trunk, the pain is nociceptive, as damage of the conducting elements does not occur per se (Zusman 2008). The presence of PNS may be detected through careful clinical examination of neurodynamic tests and nerve trunk palpation. Pathophysiological changes in non-neural tissues adjacent to the peripheral nerve may induce physiological and physical changes of the nerve and the development of PNS, which can be identified through careful assessment (Nee & Butler, 2006). Cranial neural tissues may be inherently vulnerable to abnormal neural dynamics and consequent inflammation due to the unique relationships to cranial non-neural structures.

3.1. Appropriate Clinical Testing

- Associated with activity or postures that reduce mechanosensitivity of the involved neural structures.

- Neurodynamic test may be relevant due to the increased mechnanosensitivity.

- Palpation may be mechanosensitive caused by the increased c- fiber input related with the intraneural inflammation.

- Changed adjacent tissue of the nerve which may be influence movement behavior of the nerve.

- Motor function as target tissue of the involved nerve, mostly expressed in endurance and coordination disturbances.

- Radiologic and electrodiagnostic data are not supporting.

Less appropriate

- Conduction test may be less relevant. If present then often change after neurodynamic testing and or trial treatment. And if the conduction tests are abnormal then that would probably indicate some form of CN.

3.2. Clinical classification of cranioneurodynamic testing

During PNS, neurodynamic tests may be most responsive. A diagnosis of cranial PNS is established through comprehensive examination by a process of neurodynamic tests to induce mechanical loading on the cranial neural system. We propose 3 categories of tests to load different parts of the system (including nerve trunks) to determine the presence of a cranial PNS disorder.

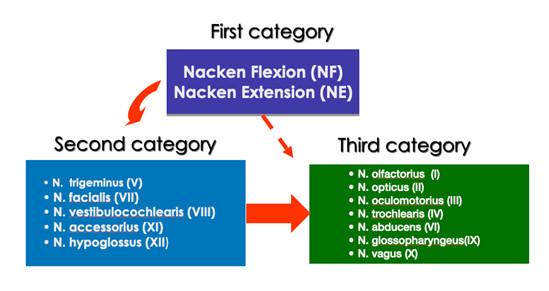

- The first category is the most fundamental which mechanically challenges the brainstem and the nerve entry zones as well as the tissues in the CPA by upper cervical flexion/extension.

- The second category. These tests are relatively simple and can be used to screen a broad spectrum of patients with cranial dysfunction and pain with a cranial neural involvement. These are the 'key' cranial nerves including the trigeminal (V), facial (VII), vestibulocochlear (VIII), accessory (IX) and hypoglossal (XII) nerves (Von Piekartz 2007).

- The third category evaluates the remaining cranial nerves which are no less important but are encountered in certain specific pathologies and symptoms. These tests are for the olfactory (I), optic (II), oculomotor (III), trochlear (IV), abducens (VI), glossopharyngeal (IX) and vagal (X) nerves (Von Piekartz 2007).

An overview of the decision-making process to test cranial neural tissue mechanosensitivity in patients with craniofacial pain is shown below:

Overview of testing for cranial neural tissue mechanosensitivity in patients with craniofacial pain (von Piekartz and Hall 2018).

During assessment an overlap of the 3 sub- classification may exist which is important for the estimation of the management strategies and prognosis as proposed below.

3.4.Assessment and Management Goals

- Detecting mechanosenstivitity and if possible, the region of increased mechanosensitivity along the nerve.

- Proving if the associated adjacent tissue around the nerve is related to the increased mechanosensitivity.

- Advocate normal (functional) movement of the peripheral nerve without severe inflammation.

- Stimulating target tissue activity by mental practice and movement without pain experience, facilitation normal nerve conduction and reduce body disruption.

Summary of assessment and management

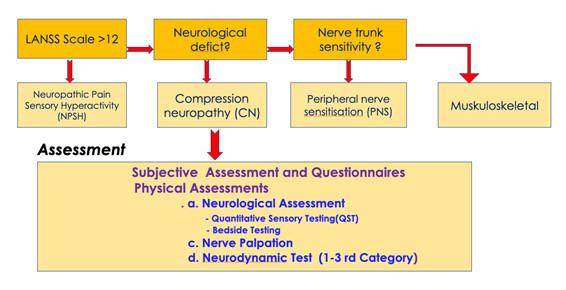

- The order of diagnosis should be NPSH, CN, PNS and musculoskeletal pain. In the absence of a positive LANSS, the next priority is CN.

- Thirdly, diagnosis of PNS is based on an absence of NPSH and CN, but in the presence of signs of mechanosensitive neural tissue. This is the group most likely to respond to neural mobilization techniques.

- Finally, in the absence of any of the features in the previous 3 criteria, patients would be classified as having musculoskeletal pain for example an artogenous, myogenous or mixed TMD.

Hierarchical classification of cranial neural pain disorders into specific neural sub-groups with proposed assessments (von Piekartz and Hall 2018).

Bernard Taxer, Harry von Piekartz

References

- Nee, R. and D. S. Butler (2006). "Management of peripheral neuropathic pain: Integrating neurobiology, neurodynamics, and clinical evidence." Physical Therapy in Sport 7: 36-49.

- Moloney, N. A., T. M. Hall, A. M. Leaver and C. M. Doody (2015). "The clinical utility of pain classification in non-specific arm pain." Man Ther 20(1): 157-165.

- Von Piekartz, H. J. M. (2007). Craniofacial pain: Neuromusculoskeletal assessment, treatment and management. Edinburgh, Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Von Piekartz J, Hall T, Clincial classification of cranial neuropathies, in Temporomandibular Disorders. Manual Therapy, exercise and needling, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Mesa Jimenez J , Handspring Publishing, chapter 14;205-271

- Smith, R. D. Treede and T. S. Jensen (2016). "Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice." Pain 157(8): 1599-1606.

- Treede, R. D., T. S. Jensen, J. N. Campbell, G. Cruccu, J. O. Dostrovsky, J. W. Griffin, P. Hansson, R. Hughes, T. Nurmikko and J. Serra (2008). "Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes." Neurology 70(18): 1630-1635

- Schӓfer, A., T. M. Hall, K. Ludtke, J. Mallwitz and N. K. Briffa (2009). "Interrater reliability of a new classification system for patients with neural low back-related leg pain." J Man Manip Ther 17(2): 109-117.

- Schӓfer, A. G., T. M. Hall, R. Rolke, R. D. Treede, K. Ludtke, J. Mallwitz and K. N. Briffa (2014). "Low back related leg pain: an investigation of construct validity of a new classification system." J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 27(4): 409-418.

- Zusman, M. (2008). "Mechanisms of peripheral neuropathic pain: Implications for musculoskeletal physiotherapy." Physical Therapy Reviews 13(5): 313-323.

Manual Cranial Therapy

Cranial manual therapy means: assessment and treatment of the cranium..

Read more..

Pain Education

“pain neuroscience education (PNE)” or “Explain Pain” is a therapeutic tool...

Read more..

Headache (HA) in children

What can the (specialized) physical therapist mean for this pain suffering group..

Read more..

Assessment Bruxism

Assessment and Management of Bruxism by certificated CRAFTA® Physical Therapists

Read more..

Clinical classification of cranial neuropathies

Assessment and Treatment of cranial neuropathies driven by clinical classification..

Read more..

Functional Dysphonia

Functional Dysphonia (FD) is a condition characterized by voice problems in the absence of a physical laryngeal pathology.

Read more..

Body Image and Distorted Perception

Body Image and Distorted Perception of One's Own Body – What Does This Mean?

Read more..

TMD in Children

TMD affects not only adults, but it also occurs frequently in children and adolescents..

Read more..