Epidemiologie

Temporomandibuläre Dysfunktionen (TMD) betreffen nicht nur Erwachsene, sondern treten auch häufig bei Kindern und Jugendlichen auf. Die Prävalenz variiert in der Literatur stark (7–60 %), abhängig vom Alter, der Population und den verwendeten Diagnosekriterien (Ekberg et al., 2023; Minghelli, 2014).

Temporomandibuläre Dysfunktionen (TMD) betreffen nicht nur Erwachsene, sondern treten auch häufig bei Kindern und Jugendlichen auf. Die Prävalenz variiert in der Literatur stark (7–60 %), abhängig vom Alter, der Population und den verwendeten Diagnosekriterien (Ekberg et al., 2023; Minghelli, 2014).

Mädchen haben ein signifikant höheres Risiko für TMD, insbesondere ab der Pubertät. Häufige Symptome sind Schmerzen im Kieferbereich, Gelenkgeräusche, Kaubeschwerden und Kopfschmerzen. Forschungsergebnisse zeigen auch, dass psychosoziale Faktoren wie Stress und parafunktionelle Gewohnheiten sowie muskuloskelettale Faktoren im Nacken- und Schädel-Gesichtsbereich zur Entwicklung der Symptome beitragen (Minghelli, 2014; Al-Khotani et al., 2016).

Obwohl die meisten Beschwerden mild sind, kann eine Untergruppe von Kindern erhebliche Einschränkungen erfahren und ein erhöhtes Risiko für Chronifizierung und muskuloskelettale Schmerzsyndrome im Erwachsenenalter haben (Al-Khotani et al., 2016; Mélou et al., 2023). Epidemiologische Daten zeigen, dass TMD häufig in der Pubertät zunimmt und in einigen Populationen mehr als ein Drittel der Kinder betrifft (Macrì et al., 2022; Rentsch et al., 2023).

Die American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2023) berichtet, dass die Prävalenz von schmerzbezogenen TMD bei Jugendlichen auf der Grundlage von DC/TMD zwischen 7 % und 30 % liegt. Eine frühzeitige Erkennung und ein multidisziplinärer Ansatz sind daher unerlässlich, um die Lebensqualität zu verbessern und langfristige Beschwerden zu verhindern, wobei auch eine CRAFTA®-Therapeut in mitwirken kann.

Klinische Untersuchung

Im Rahmen von CRAFTA® wenden wir einen systematischen und objektiven Ansatz für die klinische Untersuchung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Kiefergelenkserkrankungen (TMD) an. Die Untersuchung beginnt mit:

Im Rahmen von CRAFTA® wenden wir einen systematischen und objektiven Ansatz für die klinische Untersuchung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Kiefergelenkserkrankungen (TMD) an. Die Untersuchung beginnt mit:

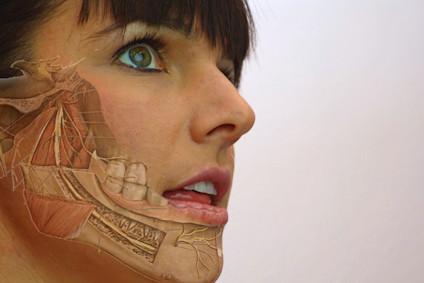

- Einer gründlichen Observation des Gesichts, einschließlich der Position und Größe des Unterkiefers und des maxillofazialen Bereichs, um Asymmetrien oder Wachstumsstörungen festzustellen;

- Einer klinischen Beurteilung der Funktion des Kiefergelenks (TMJ), einschließlich der physiologischen Kieferbewegungen (sowohl aktiv als auch passiv – insbesondere Mundöffnung und -schließung), gefolgt von passiven Kieferbewegungen( physiologische und Zusatzbewegungen) , der Beobachtung von Gelenkgeräuschen und Blockaden unter Berücksichtigung altersbezogener Grenzwerte (Rongo et al., 2021, von Piekartz 2007,2015, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry [AAPD], 2024);

-

Palpation der Kaumuskulatur wie des Masseters und des Temporalis sowie[DvP1] Testung des M. pterygoideus lateralis durch Beurteilung der akzessorischen und physiologischen Bewegungen des Kiefergelenks und der Triggerpunkte sowie der sekundären Muskeln wie des M. sternocleidomastoideus, des M. trapezius und der tiefen Halsmuskulatur, durchgeführt nach standardisierten Protokollen.

Das Ziel besteht darin, temporomandibuläre Dysfunktionen (TMD) im Zusammenhang mit arthrogenen, myogenen oder neurogenen Anzeichen, die sich in bestimmten klinischen Mustern äußern, zu erkennen und diese Befunde mit den individuellen Symptomen des Kindes in Verbindung zu bringen

Neben dem Kiefergelenkbereich umfasst die systematische Beurteilung auch

- die kraniozervikale Region, wobei der Schwerpunkt auf der Dysregulation der Arthrokinematik und der Schmerzprovokation von C0–C2/3 liegt;

- die kraniofaziale Region, in der Asymmetrien und Funktionsstörungen der maxillofazialen Strukturen mithilfe passiver Techniken identifiziert werden, wobei drei Parameter bewertet werden: subjektive Reaktion, Widerstand und Rebound (siehe CRAFTA®-Statement zur kraniofazialen manuellen Therapie);

- die Funktion der kraniofazialen Organe, wobei mögliche Funktionsstörungen des Gehörs, des Sehvermögens, des Mundes und der (nasal-diaphfragmatischen) Atmung und der Zungenposition bewertet werden, die alle in funktioneller Beziehung zur optimalen Funktion des Kiefergelenks stehen.

- Kranio-neurale Aspekte: Es gibt Hinweise darauf, dass das Wachstum des Schädels und der neuralen Strukturen nicht immer synchron verläuft und es zu Diskrepanzen zwischen Neurokranium und Viszerokranium kommen kann. Diese können die Spannungsverteilung in den Hirnhäuten und im Nervengewebe beeinflussen und möglicherweise zu einer erhöhten Mechanosensitivität beitragen (Carlson, D. S., & Buschang, P. H. (2022). Der pädiatrische Long-Sitting-Slump-Test, der zur Beurteilung der Mechanosensitivität der Neuraxis und des umgebenden Bindegewebes verwendet wird, ist sehr hilfreich. Ein positiver Test – bei dem die Beugung des Rumpfes und der Halswirbelsäule Schmerzen oder sensorische Veränderungen hervorruft – kann auf eine erhöhte neuronale Spannung hinweisen, die zu orofazialen Beschwerden beiträgt (White and Pape 1992, von Piekartz et al 2007).

Diese umfassende Beurteilung stellt sicher, dass nicht nur lokale Beschwerden, sondern auch sekundäre oder damit verbundene Funktionsstörungen erkannt werden. Das Ergebnis ist ein integriertes Modell, in dem klinisches Fachwissen, externe Erkenntnisse und kinderspezifische Anpassungen zusammenfließen, um eine zuverlässige und valide Diagnostik zu ermöglichen (AAPD, 2024; Rongo et al.,2021).

Diese umfassende Beurteilung stellt sicher, dass nicht nur lokale Beschwerden, sondern auch sekundäre oder damit verbundene Funktionsstörungen erkannt werden. Das Ergebnis ist ein integriertes Modell, in dem klinisches Fachwissen, externe Erkenntnisse und kinderspezifische Anpassungen zusammenfließen, um eine zuverlässige und valide Diagnostik zu ermöglichen (AAPD, 2024; Rongo et al.,2021).

Behandlung und Management

Die Behandlung und das Management von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit TMD im Rahmen von CRAFTA® basieren auf einem integrierten Ansatz für die verschiedenen betroffenen Regionen:

Stufe 1

- in erster Linie die Kiefergelenkregion, aber auch die kraniofaziale, kranioneurale und kraniozervikale Region, die mit den Zeichen und Symptomen der Kiefergelenkserkrankung in Zusammenhang stehen können. Manuelle Therapie und manuelle Techniken werden mit funktioneller Bewegungstherapie kombiniert, die auf die Zungenfunktion, die Atmung, das Schlucken usw. abzielt. Dadurch wird sichergestellt, dass nicht nur lokale Symptome, sondern auch sekundäre Funktionsstörungen behandelt werden. Eine multimodale Rehabilitation, die manuelle Therapie, Bewegungstherapie und Selbstmanagementstrategien kombiniert, hat sich als wirksam bei der Schmerzlinderung, der Verbesserung der Mundöffnung und der Optimierung der Kaufunktion erwiesen (Garrett et al., 2025).

Stufe 2

Zusätzlich zu den somatischen Komponenten befasst sich die CRAFTA®-Therapeutin auch mit psychosozialen Faktoren (Iodice et al 2024).

Zusätzlich zu den somatischen Komponenten befasst sich die CRAFTA®-Therapeutin auch mit psychosozialen Faktoren (Iodice et al 2024).- Die Aufklärung über die Neurowissenschaften des Schmerzes wird individuell auf das Kind und seine Eltern zugeschnitten, indem die Ursachen des Schmerzes, der Einfluss emotionaler und kognitiver Faktoren sowie abnormale motorische Funktionsstörungen wie parafunktionelle Gewohnheiten (z. B. Bruxismus) erklärt werden;

- Konditionierungstechniken wie die Gewohnheitsumkehrtechnik (HRT), orofaziale mentale Ablenkungstechniken und unterstützende Verhaltensänderungen, einschließlich Tagesabläufen und Schlafhygiene, können die Belastung der Kiefergelenke reduzieren;

- Einbeziehung neuer Entwicklungen wie E-Health (spezialisierte Apps) und Telerehabilitation. Diese bieten zusätzliche Möglichkeiten zur kontinuierlichen Begleitung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit TMD, mit einer vergleichbaren Wirksamkeit wie die persönliche Therapie(Garrett et al., 2025).o Dies steht im Einklang mit dem biopsychosozialen Ansatz, der zunehmend zum Standard in der TMD-Behandlung wird und dessen Schwerpunkt auf der Erkennung von Stress, Bewegungsangst und Lebensstilfaktoren liegt, die die Schwere und Persistenz der Symptome beeinflussen;

- Untersuchungen zeigen, dass die multidisziplinäre Zusammenarbeit die Behandlungsergebnisse bei Kindern mit TMD deutlich verbessert. Neben der neuromuskuloskelettalen Therapie spielen Logopäden, Zahnärzte, Kieferchirurgen, Kieferorthopäden und Dentalhygieniker[DvP1] eine wichtige Rolle, beispielsweise bei der Mundhygiene und der Kieferfunktion (Aldayel et al 2023). Selbstversorgung und Aufklärung bilden eine gemeinsame Grundlage, wobei die CRAFTA®-Therapeutin stets mit anderen Disziplinen zusammenarbeitet, um eine optimale Versorgung zu gewährleisten (Al-Khotani et al., 2016; Ohrbach & Dworkin, 2016);

- Eine langfristige Überwachung ist unerlässlich. Angesichts der Wachstumsphasen von Kindern streben CRAFTA®-Therapeuteninnen an, alle 3 bis 6 Monate eine Neubewertung vorzunehmen, um Maßnahmen wie Lebensstilberatung und Übungen nach Bedarf anzupassen.

Harry von Piekartz, Daniela von Piekartz

References

- Aldayel, A. M., AlGahnem, Z. J., Alrashidi, I. S., Nunu, D. Y., Alzahrani, A. M., Alburaidi, W. S., Alanazi, F., Alamari, A. S., & Alotaibi, R. M. (2023). Orthodontics and temporomandibular disorders: An overview. Cureus, 15(10)

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry [AAPD], 2024). https://www.aapd.org

- Al-Khotani, A., Naimi-Akbar, A., Albadawi, E., Ernberg, M., & Christidis, N. (2016). Prevalence of diagnosed temporomandibular disorders among children and adolescents in Saudi Arabia. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 17(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0642-9

- Carlson, D. S., & Buschang, P. H. (2022). Craniofacial Growth and Development. Orthodontics-E-Book: Orthodontics-E-Book, 2.

- Ekberg, E., Nilsson, I. M., Michelotti, A., Al-Khotani, A., Alstergren, P., Conti, P. C. R., ... & Rongo, R. (2023). Comprehensive and short-form adaptations for adolescents: Comprehensive and short-form adaptations for adolescents. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 50(11), 1167-1180.

- Garrett, A., Biasotto‐Gonzalez, D. A., Niszezak, C. M., Tosi, A. G., Santos, G. M., & Sonza, A. (2025). Multimodal Physiotherapeutic Treatment in Adolescents With Temporomandibular Disorders: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation.

- Macrì, M., Murmura, G., Scarano, A., & Festa, F. (2022). Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders and its association with malocclusion in children: a transversal study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 860833.

- Mélou, C., Sixou, J. L., Sinquin, C., & Chauvel-Lebret, D. (2023). Temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents: A review. Archives de Pédiatrie, 30(5), 335-342.

- Minervini, G., Franco, R., Marrapodi, M. M., Fiorillo, L., Cervino, G., & Cicciù, M. (2023). Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents evaluated with Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders: a systematic review with meta‐analysis. Journal of oral rehabilitation, 50(6), 522-530.

- Ohrbach, R., & Dworkin, S. F. (2016). The evolution of TMD diagnosis: past, present, future. Journal of dental research, 95(10), 1093-1101

- Rentsch, M., Ettlin, D., & Kellenberger, C. J. (2023). Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders based on a shortened DC/TMD symptom questionnaire in children and adolescents aged 7–14 years. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(12), 4109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124109

- Iodice, G., Michelotti, A., D’Antò, V., Martina, S., Valletta, R., & Rongo, R. (2024). Prevalence of psychosocial findings and their correlation with TMD symptoms in an adult population sample. Progress in Orthodontics, 25(1), 39.

- Rongo, R., Ekberg, E., Nilsson, I. M., Al‐Khotani, A., Alstergren, P., Conti, P. C. R., ... & Michelotti, A. (2021). Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for children and adolescents: an international Delphi study—part 1‐development of Axis I. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 48(7), 836-845.

- The slump test. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(3), 271-274.

- von Piekartz, H. J., Schouten, S., & Aufdemkampe, G. (2007). Neurodynamic responses in children with migraine or cervicogenic headache versus a control group. A comparative study. Manual Therapy, 12(2), 153-160.

- Von Piekartz, H. J. (2007). Craniofacial pain: neuromusculoskeletal assessment, treatment and management. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Von Piekartz, H. J. (2015). Kiefer, Gesichts-und Zervikalregion. In :. Thieme., Stuttgart

Headache (HA) in children

What can the (specialized) physical therapist mean for this pain suffering group..

Mehr lesen..

Assessment Bruxism

Assessment and Management of Bruxism by certificated CRAFTA® Physical Therapists

Mehr lesen..

Clinical classification of cranial neuropathies

Assessment and Treatment of cranial neuropathies driven by clinical classification..

Mehr lesen..

Funktionelle Dysphonie

FD ist eine oft unterschätzte Erkrankung, die Personen betrifft, die ihre Stimme beruflich oder privat intensiv nutzen..

Mehr lesen..

Körperbild und verzerrte Wahrnehmung

Körperbild und verzerrte Wahrnehmung des eigenen Körpers - Was bedeutet das?

Mehr lesen..

TMD bei Kindern

TMD betreffen nicht nur Erwachsene, sondern treten auch häufig bei Kindern..

Mehr lesen..